Derek Cianfrance knows the pains of relationships, and the beauty in their tragedy. He knows that we hurt ourselves by fighting for something as doomed as it is life-affirming. We make choices that may seem outrageous to outsiders because they don’t understand what it means for someone else to be a part of you. Even if one day, they are no more than a memory. Those choices are more difficult still if one tries to stay true to oneself, so that he/she can look themselves in the mirror and respect what they see. It’s an impossible balance akin to acceptance of pain, because even if the pain is not worth it in the end, it was worth it for a time. Perhaps that’s why we often feel that time is stolen from us, until we remember that it’s the greatest gift we have.

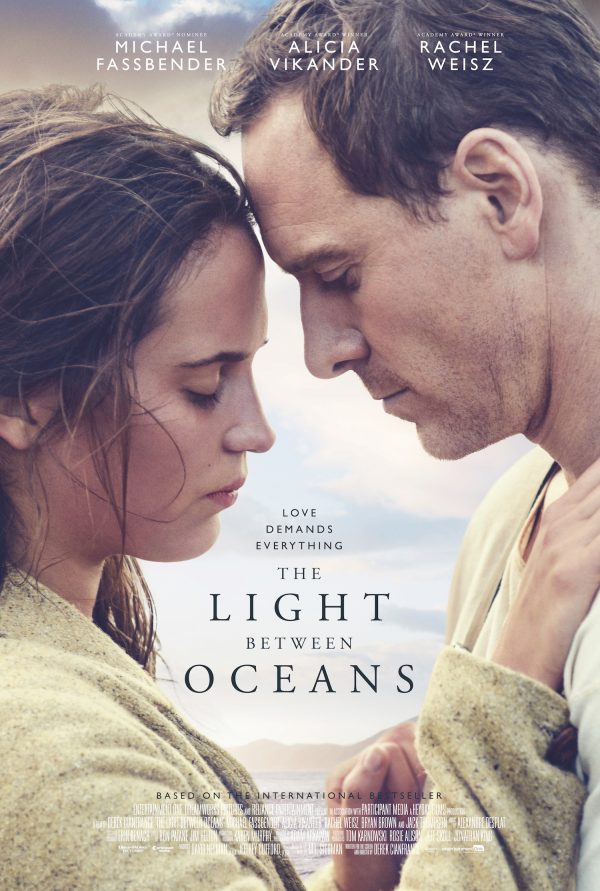

Cianfrance’s new film, The Light Between Oceans, is one about people making catastrophic decisions because of love, whether that be the love of a child, or a soulmate. And these choices are thrusted upon the characters through no faults of anyone but the cruelty of fate, disguised as a blessing. Yes, the decisions that they make are ultimately poor ones, but when a choice must be made with emotion because reason has been ripped from you, then your choices are poor no matter how rightly they are justified. The film struggles at times (meaning it’s entire second half) by descending into melodrama, but it’s performances and sheer beauty elevate it into a rare philosophical adult fare, unlike most of the films you’ll see in 2016.

The film introduces us to a subdued World War I veteran, Tom Sherbourne (Michael Fassbender), who takes a job as a lighthouse keeper on a remote island off the western coast of Australia. During his brief time on the mainland, he meets and falls in love with a local woman, Isabel (Alicia Vikander), who agrees to be his wife. She comes to live with him at the lighthouse, and the two of them seemingly have a perfect paradise to share. But joy turns to depression as Isabel becomes pregnant twice and, on both occasions, loses the child. Then, miraculously, they are given a chance to be parents in the form of a stray rowboat that carries a dead man, and his living infant daughter.

This opening half of the film was my favorite half. Cianfrance is best know for the grim, gritty, and original Blue Valentine. He replaces that grit with polish, and originality with a more by the numbers narrative here, but that didn’t matter to me. The film is a feast for the eyes, as golden horizons and wind-graced, tearful faces populate it’s sights. Even the times when it’s visually muted, Cianfrance and his cinematographer, Adam Arkapaw, paint with a delicate brush. It helps that these visuals are aided by an elegant score from the underrated Alexandre Desplat. This segment of the film reminded me of what I thought was the most heart-breaking aspect of Blue Valentine, which was to see the happier moments of a relationship’s past, while knowing the pain they’d bring. As joyful and in-love as I felt that Tom and Isabel were, I could see the dark that would follow their sunset horizons. And it was a painful feeling.

The narrative could be argued as one that’s too convenient for things to move forward. And while that argument has merit through it’s characters making seemingly insane choices, I don’t think it applies to the films coincidences. After all, if you think about how any two partners meet each other in life, you’ll find that it takes a large series of choices in order for it to be possible. Still, the film became a bit of a slog for me in it’s second half where Tom discovers that the lost-at-sea baby was presumed dead and is being mourned by her mother (Rachel Weisz). Unable to cope with his role in her grief, he makes rash decisions that made me want to slap him, even though I understood why he was making them. The real problem is due to the film’s pacing in this section. The story grinds too slow to feel the thunder of the tragedy that should have been coming like a freight train. Instead, that tragic train just kind of pulls into the station and stays there, causing it to have less impact. Worst of all is that the film’s ending, which contains perhaps it’s saddest scene, felt too rushed and too convoluted to earn the tears it was trying to pull from me.

With saying all of that, I almost cried because of Michael Fassbender and Alicia Vikander. Fassbender is reserved until he has reasons to let go of his emotions, which thankfully happens quite often. Vikander made me fall in love with her, and in so doing, made me want to help her through her character’s darkest moments, in which she appears so grief-stricken that it boarders on mentally unstable. The two performers became a real-life couple as a result of filming The Light Between Oceans, and they both made me see why. Rachel Weisz has a role that, despite the character being in the absolute right, begins as an antagonist, but her performance is able to get past anything black or white.

There’s a lot of things that I loved about this film, but it’s second half, at times, can be as long-winded as it is windy. I suppose I’ll choose to look at it like a failed relationship, in which certain things leave a bad taste, but those things don’t take away from the positive highs. And while the lows are there to learn from, the highs are what should be remembered.

Grade: B

One thought on “The Light Between Oceans”